Epstein-Barr virus: a hot topic at the ECTRIMS research conference

This week, researchers from across the globe gathered together in Milan for ECTRIMS – the world’s largest MS research conference. Three new pieces of research were presented focusing on EBV.

One of the hot topics at the conference was Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) – a common type of herpes virus. Nine in ten adults will be infected with EBV in their lifetime. But many people will experience no symptoms.

For several decades, we’ve known there’s a link between EBV and MS. But there are still a lot of unanswered questions. At the conference, researchers showed some exciting results which might start to answer these questions.

EBV and MS genes

No one knows for sure why people get MS. It's likely to be due to a mix of genes, something in your environment and some lifestyle factors. One genetic risk factor is the HLA-DR gene. One environmental factor is EBV. But we don't know if these factors are linked.

Professor Christian Münz from the University of Zurich has been studying EBV for more than 20 years. He found that when mice had one form of the HLA-DR gene, the immune system was less able to control an EBV infection.

This could mean for people with this gene, EBV might activate the immune system to mistakenly attack myelin. But we need more research to find out if this is true for people with MS.

Read more about MS and genetics

EBV and risk of developing MS

Professor Albert Ascherio is from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He presented the findings of a recent study into whether being infected with EBV affects the risk of developing MS

They used information from 10 million people from the US military. They found the risk of developing MS was 32 times higher when someone had an EBV infection. This suggests that EBV could play a role in causing MS.

Read more about their study in our news story from 2022

EBV and the immune system

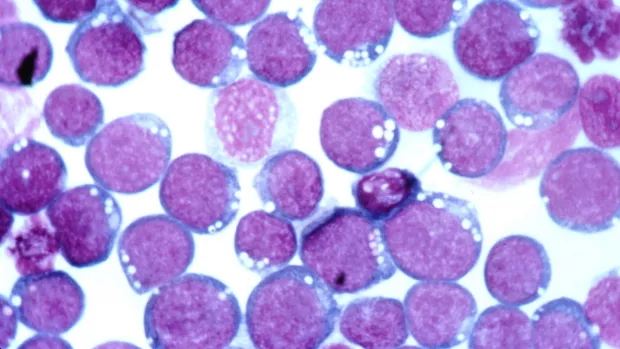

In autoimmune conditions, your immune system will attack and damage your body's own tissues. EBV is associated with several autoimmune conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus and MS.

Professor William Robinson from Stanford University highlighted a number of ways in which EBV could be driving these autoimmune conditions.

One way is called molecular mimicry. This is where a part of the virus looks like a molecule found naturally in the body. The immune system should just recognise the virus and destroy it. But in autoimmune conditions it mistakes the molecule for the virus and attacks the body’s own tissues instead. A part of EBV looks similar to myelin. So this could be true for myelin in the brain.

Read more about viruses and MS

Our research into EBV and MS

As we’ve seen at the ECTRIMS conference this year, EBV is an important area of research in MS. But questions still remain about exactly how MS and EBV are linked. We’ve recently committed to funding two studies focused on this topic.

Which cells does Epstein Barr virus affect in MS?

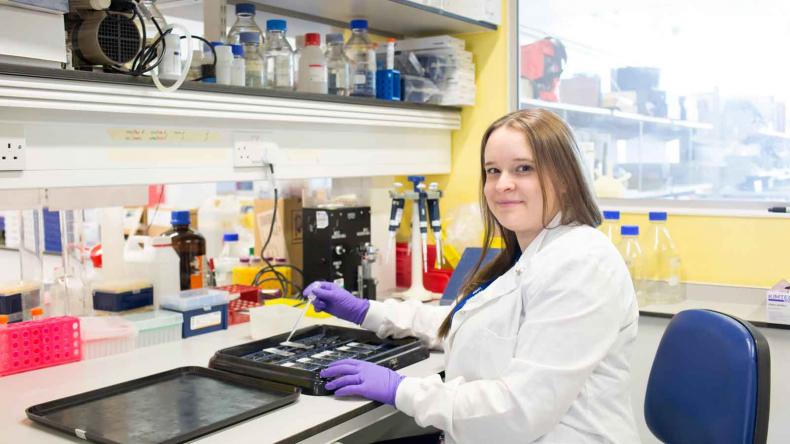

Professor Ruth Dobson at Queen Mary University of London will use blood samples to look for EBV in people with MS and without MS. Her team will test whether there's a different amount of EBV in these two groups. And using a special technique, they'll be able to work out which type of cells the EBV has come from.

This project will help us understand where EBV is hiding in the body. And if it's different in people with MS. If EBV is behaving differently in people with MS, it might tell us why the infection sometimes leads to MS.

If we know where EBV is hiding, we know which cells we should aim treatments at. This could reduce the effects of EBV in the body.

Read more about our research into which cells the EBV virus affects

How could EBV trigger MS?

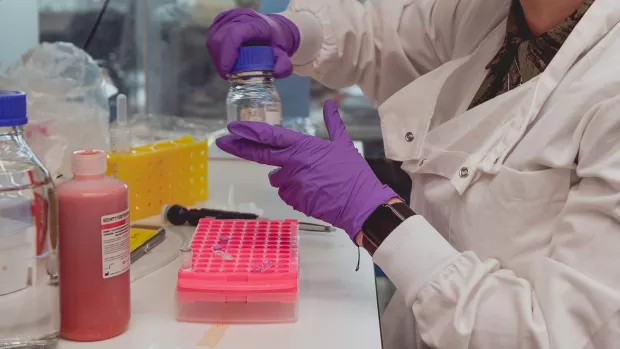

Dr Claire Shannon-Lowe at University of Birmingham will collect immune cells from spinal fluid and blood of people with MS. They’ll look for EBV-infected cells to find how the infection has changed the cells.

The team hope to find changes in EBV-infected cells which can be detected in the blood. Then, future research could make new treatments to kill only these cells. This would reduce the side effects of current immunotherapies. This is a long-term aim, but only with this initial work will it ever be possible.