Developing PET imaging to identify types of MS lesions

- Lead researcher:

- Professor Franklin Aigbirhio

- Based at:

- University of Cambridge

- MS Society funding:

- £122,971.00

- Status:

- Starting in January 2023

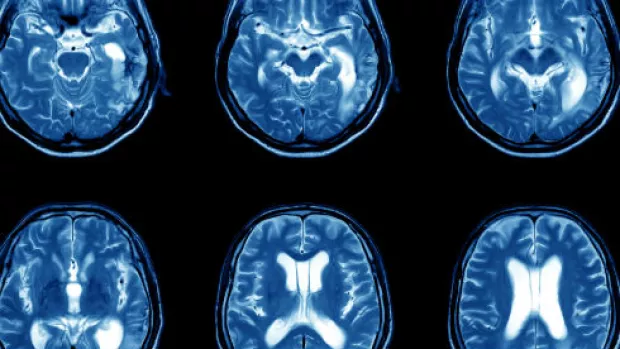

One of the key steps to stopping MS is finding treatments that can repair myelin. We’ve reached an exciting milestone where we’re beginning to see potential myelin repair treatments tested in trials. But not all MS lesions are the same, so one type of myelin repair treatment might not work for everyone’s MS. It depends what’s stopping healthy myelin repair from happening. Professor Franklin Aigbirhio hopes advanced imaging technology could to help identify which treatments could work in different people.

Background

When myelin is damaged the brain’s resident stem cells, called oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), begin the repair process by transforming into oligodendrocytes. These are a special type of brain cell that can make myelin and put it back on the nerve.

Researchers have already found ways to kick-start this cell transformation. But in some types of chronic MS lesion there aren’t many OPCs, so this type of treatment might not help.

At the moment we have no way to find out how many OPCs a person with MS has in their lesions. So there’s no way to tell if this type of treatment would work well for their MS. We could potentially trial treatments on the wrong people, giving misleading results.

About the project

Professor Aigbirhio hopes to address this problem using PET imaging.

The project aims to develop a new radiotracer which sticks to OPCs in the brain. When PET scanned, it could allow us to find out how many OPCs people have in their MS lesions. And it could enable clinicians to determine whether a patient has enough OPCs to benefit from a type of myelin repair treatment.

The team will modify and improve existing radiotracers developed by pharmaceutical companies. They’ll test them in tissue from the MS Society’s Tissue Bank, and carry out PET imaging in mice or rats to see if they can successfully image OPCs.

How will it help people with MS?

If results from the project are positive, Professor Aigbhirio hopes to test the technology in people with MS.

Developing a way to identify types of MS lesions could ensure we’re testing drugs in trials as accurately as possible. And it could help personalise treatments for MS in the future.

What is PET?

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a highly sensitive clinical imaging technology which enables scientists to visualise small cellular changes in the body. This is before changes may be seen using other advanced imaging techniques like MRI and CT scans.

PET is becoming widely used in the NHS for cancer diagnosis. A person is injected with a radioactive substance (called a radiotracer) which is designed to stick to specific cells in the body.

A PET scanner can then detect where in the body the radiotracer has stuck, and creates an image. For example, it could show where cancerous cells have spread in the body.

It’s important to note that the amount of radioactivity associated with a standard PET scan, is safe. The radiopharmaceutical quickly becomes less radioactive over time and will be passed out of the body naturally within a few hours or less.