Artificial intelligence spots new patterns in MRI

Dr Arman Eshaghi from University College London used artificial intelligence to analyse thousands of MRI brain scans in MS. Research Network member Dominic Shadbolt spoke to Arman and told us what it revealed.

Have you ever wanted to see into the future? Well, we can’t offer you the winning lottery ticket numbers, but soon we might be able to predict some things about MS. Artificial intelligence (AI) isn't sci-fi anymore.

What is AI?

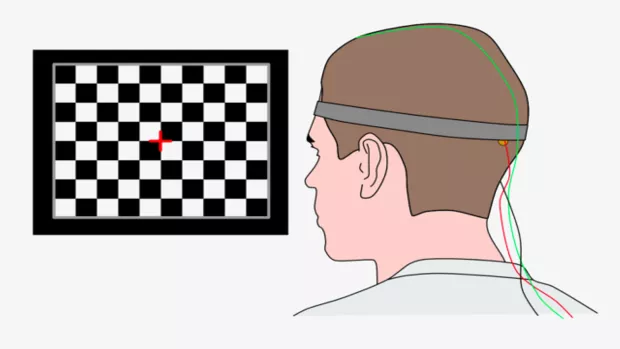

AI uses computers to do things that would normally rely on human intelligence. The use of computers greatly reduces the time it takes. In MS, clinical trials can include hundreds or thousands of participants. It would take a human a really long time to analyse all those scans. That’s why we get a computer to do it for us.

What has the AI analysed?

Dr Arman Eshaghi used computers to look at 9,000+ brain images. Arman said: “It was nine solid months of a university super-computer working 24/7 to analyse the images.”

To analyse the scans, the AI had to learn how to play 3D chess with brain images. When someone has an MRI scan, you get a series of images of slices of the brain. So the AI had to look at each flat image and link them back together to look at the whole brain.

From there, it learnt to spot changes in the brain caused by MS, and any patterns in these changes that might tell us more about MS.

What did it find?

By comparing more MRIs than many neurologists will see in their lives, the computer has learnt to spot patterns that are very hard to see.

This huge dataset has allowed the AI to identify different subtypes of MS based on where the brain changes are and how they evolve over time.

Three new MS subtypes

The researchers describe each subtype by the first changes visible on MRI scans:

1. Changes in the volume of brain tissue in the outer part of the brain.

2. Changes in nerve cells’ ability to send messages in the inner part of the brain.

3. Areas of myelin damage concentrated in lesions, occurring early on in the condition.

By analysing so many brain scans alongside clinical data, the AI was also able to predict how people with these different sub-types are likely to progress. And even how they may respond to treatment.

More research is still needed. But Arman tells me this study and others could one day change the way we talk about the distinction between relapsing and progressive MS.

How could this help people with MS in the future?

AI could potentially give recommendations to neurologists by predicting the most suitable treatment for each individual person. In the not so distant future, it may ensure you are getting the care that’s more about you and your MS, not just MS in general. I hope this will be possible for both relapsing and progressive MS in the future, as more treatments emerge.

AI could also give the neurologist your MRI scan with its observations, highlighting early signs of progression that may be brewing, that a human can’t necessarily spot yet. This could allow you, and the doctor, to make better decisions or give you a bit more certainty about your future.

Arman is hopeful we’ll see this technology moving from clinical trials into clinical practice in the next five years. And in ten years, it could become a pretty standard part of how our MRIs are analysed. Personally, I can’t wait!

This blog came from an article in MS Matters - access the issue and the full back catalogue via our website.

If you'd like to find out more about Arman's work you can read Arman's study in full on the journal website.