People with progressive MS have 'older' neural stem cells

Researchers have found the neural stem cells of people with primary progressive MS appear to be older than they are. And this could stop myelin-making cells from developing normally.

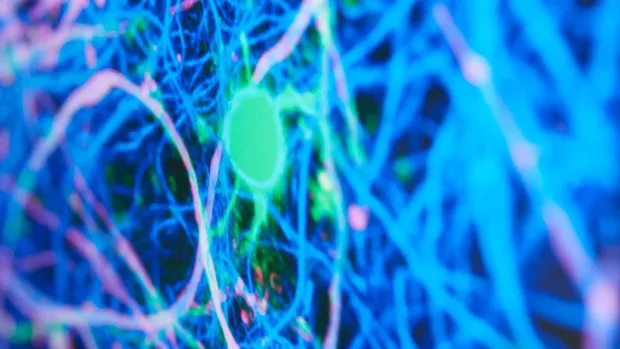

Brain stem cells look older than they are

As we age, so do our cells. This process is called senescence and it’s a normal part of natural ageing. But it can also be caused by inflammation, which we know causes damage in MS.

This new study, led by researchers at the University of Connecticut, found the brain stem cells of people with primary progressive MS also look older than they are. These cells look decades older when compared to similar cells from people of the same age without MS.

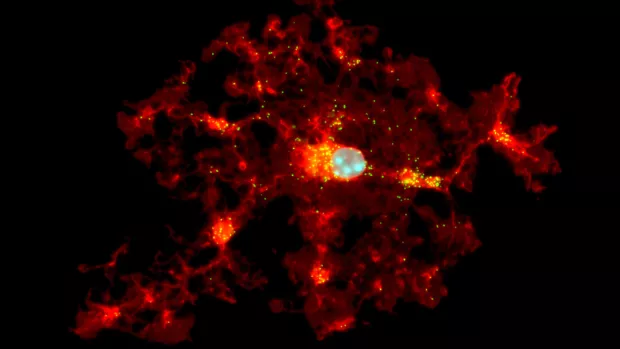

Damaged stem cells stop myelin production

Previous research has shown that brain stem cells from people with primary progressive act differently in the brain. They prevent myelin-making cells, called oligodendrocytes, from maturing and producing myelin.

This study, involving researchers at our MS Society Edinburgh Centre for MS Research, showed these cells produce high levels of a protein called HMGB1 in people in MS. And when this protein was blocked, oligodendrocytes were able to develop normally.

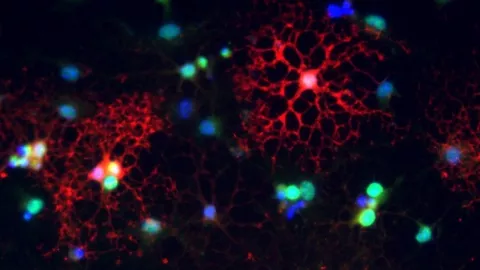

Can these changes be slowed, stopped or reversed?

The team also found that when stem cells were treated with rapamycin, a drug that suppresses the immune system, oligodendrocytes were able to develop normally. Previous studies have ruled out rapamycin as a treatment for people with relapsing MS. But this research shows it has the potential to aid myelin repair in progressive MS.

Dr Sorrel Bickley, our Head of Biomedical Research, said: “This is a really interesting study, which gives us a better insight into the association between cellular ageing and myelin repair in MS. There are currently over a dozen disease modifying therapies that target the immune system, but we don’t yet have any treatments that repair myelin. We hope further research in this area could lead to new treatments for everyone living with MS, which affects over 100,000 people living in the UK.

The next step will be to look at the brain stem cells of people with relapsing MS, to understand more about when these changes begin. And to see if they can be slowed, stopped or reversed.

Finding new ways to promote myelin repair is crucial

Dr Bickley said: “We are proud to be funding research at the MS Society Cambridge Centre for Myelin Repair, which is also looking into the impact ageing can have on myelin making cells. Finding new ways to promote myelin repair is crucial if we are to achieve our ultimate goal: to stop MS.”