A turning point for progressive MS

Stop MS Ambassador, neurologist and researcher Professor Anna Williams tells us about the latest research into progressive MS treatments and her hopes for the future.

I started looking after people with MS as a junior doctor 20 years ago. Back then there were only a few disease modifying therapies (DMTs) available for relapsing MS. But they were all ones you had to inject under the skin and many people really struggled.

In the 2000s, new DMTs started to come along that you could take as an infusion every few months or as daily tablets. They were more effective at controlling relapses and far more convenient.

That was the start of an explosion in DMTs for relapsing MS. Now it’s a completely different picture. The wealth of options means people can weigh up effectiveness and side effects to decide what’s right for them.

A new focus on progressive MS treatments

We need to see the same for progressive MS. There are only a few DMTs for people with early progressive MS. Tens of thousands of people still don’t have any treatments to change the course of their condition.

All available DMTs work by dampening down immune system attacks on myelin – the protective coating around nerves. But evidence has shown the immune system plays less of a role in progressive MS. The steady worsening of symptoms happens because the body’s natural myelin repair process stops working properly and the nerves underneath get damaged or destroyed.

To stop MS we need to repair damaged myelin and protect nerves. We’re at a real turning point now. The focus of MS researchers around the world has turned to progressive MS. My own research group in Edinburgh was established in 2008 and we’ve been focussing on myelin repair ever since.

Changing our approach

Changing the focus of MS research has meant my colleagues and I have needed new approaches that focus on what’s driving progression.

For instance, historically, researchers have used mice with brain inflammation to study relapsing MS. But those aren’t very useful for progressive MS where immune attacks are less common. Now we can use mice that better mimic features of progression like nerve damage. And it’s not just mice - my colleagues at Edinburgh are using zebrafish to watch myelin repair happening in real time.

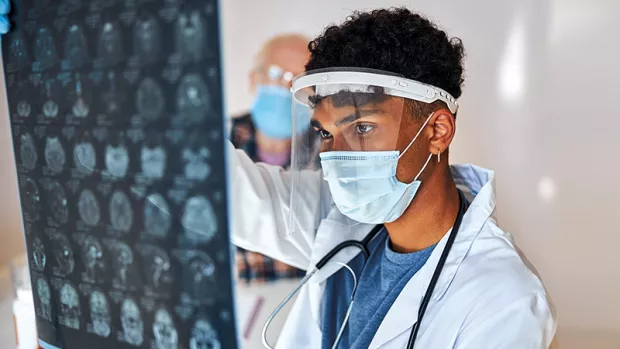

We’ve also needed to find ways to measure if potential progressive MS drugs are working. For relapsing MS, we look at lesions on MRI scans to see whether inflammation has reduced. But that can’t tell us whether myelin is being repaired. Researchers are now using new MRI and imaging techniques to better detect myelin repair in human brains.

Improving myelin repair

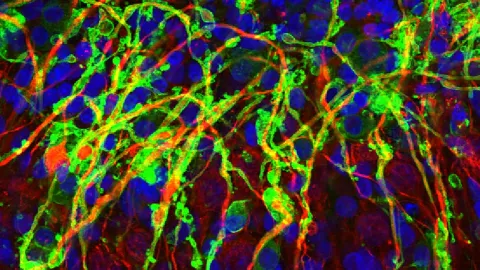

It’s tremendously exciting that several myelin repair drugs are now being tested in clinical trials but there’s still work to be done. My team are looking at how to make myelin repair as efficient as possible. For example, recently we discovered there are different types of myelin-making cells (called oligodendrocytes) and some are better than others at producing myelin.

My team is trying to find ways to encourage the formation of cells that are best at making myelin. We’re also looking at the make-up of different oligodendrocyte subtypes in of people with MS to see if that predicts how their MS will develop or how likely they are to respond to treatments.

A concerted effort

There’s a concerted global effort to crack progressive MS and I love working with scientists all over the world to tackle the problem together.

We’ve made incredible progress over the last few decades and we now have a solid platform to build on. Treatments to stop disability progression are now a very real prospect.