Thinking about HSCT? How, when and why it’s an option for MS

Neurologist Kate Petheram gives us her perspective on the MS disease modifying therapy HSCT (haematopoietic stem cell transplantation). As the multiple sclerosis lead at her hospital, Kate takes an in-depth look at how HSCT fits into MS care and treatment options on the NHS - including fertility and overseas treatment.

I’m a neurologist with a specialist interest in MS. I work in a district general hospital in Sunderland - part of the South Tyneside and Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust.

In our hospital we prescribe all the disease modifying therapies (DMTs) that are currently available. We’re working with our neighbouring neuroscience centre so we can offer HSCT locally. But until this is possible we refer patients to London and Sheffield to be considered for HSCT.

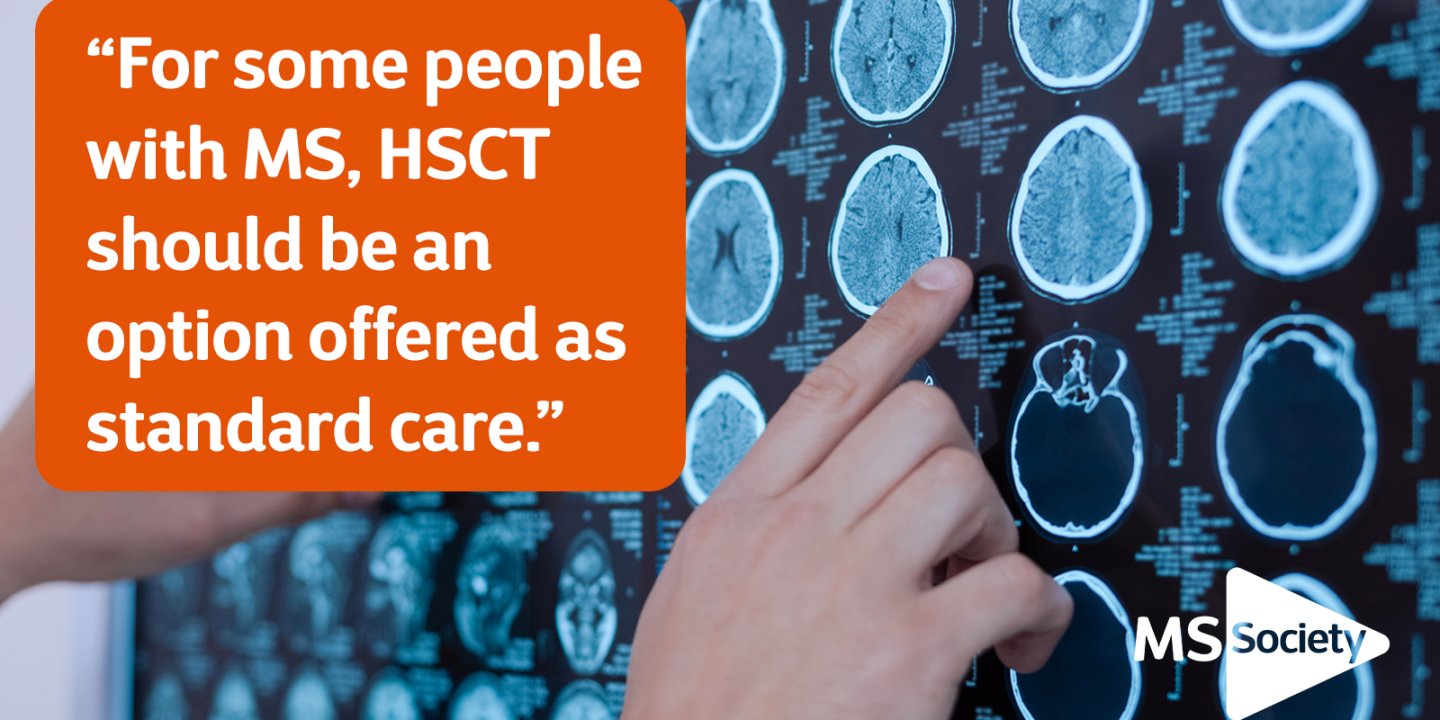

HSCT is increasingly being recognised as an effective DMT option for MS. So it should be offered as standard care on the NHS if you’re taking a highly effective DMT, but you still have ongoing inflammation. That inflammation could show up as relapses or on MRI scans. HSCT may also be an option if you haven’t yet had a DMT and you have rapidly-evolving severe MS (sometimes described as ‘aggressive’ MS).

Research has shown HSCT can be effective in these circumstances.

For some people with relapsing remitting MS, the best access to HSCT at the moment could be through the StarMS research trial. For example, if you haven’t had a DMT and you’ve got aggressive MS. Or if you have ongoing inflammation despite a moderately effective DMT like a beta interferon. Because it’s a trial, though, you might be chosen at random to receive another highly effective DMT instead.

There might be times where another DMT option suits someone better – more on this, StarMS and the research evidence later…

“It took me 3 or 4 months to come round to the idea of doing HSCT. The procedure was a big thing to get my head round. In our area there’s no MS specialist neurologist and we had to be very persistent to find out more. My wife and I did eventually speak to an MS specialist who gave us detailed information. And my GP has been great at arranging blood tests and follow-up checks since I’ve had HSCT.”

The role of the neurologist in HSCT

Most neurologists with a specialist interest in MS should be aware of HSCT as an option. If your neurologist isn't an MS specialist it’s reasonable to ask to be referred to one who is. And if you’re eligible for NHS treatment but your hospital isn’t an HSCT centre, your neurologist can refer you to either London or Sheffield.

The role of the neurologist in HSCT is mainly in seeing if someone is eligible and advising them about the benefits of HSCT in MS. The actual procedure is carried out by haematologists who’ll also explain the potential risks of the procedure. Haematologists are blood specialists.

Before we refer someone from my centre, we’d discuss eligibility at our regional MS multi-disciplinary team (MDT). That team has a mix of different health care professionals.

The follow-up care for someone who’s had HSCT will involve monitoring of bloods, risk of infection and the need for vaccinations. This is generally coordinated by the haematology team because they’re most familiar with the potential complications. How this follow-up is coordinated will vary. It depends on the arrangement of local services and where the transplant was done.

HSCT is not always first choice

In an era where we have a range of highly effective treatments for MS, access to HSCT is a big issue.

We have increasing evidence that highly effective DMTs are best given as early as possible. But there’s likely to be some delay in starting the procedure, even in centres where HSCT takes place. Not least that’s because of the work needed to make sure the procedure is as safe as possible.

So if I can treat someone with a different, highly effective, DMT within a few days sometimes that may be more appropriate. For instance, that could be a choice if they haven’t been on treatment before and they have active disease. This is one of the considerations I’ll talk through with them.

The evidence for HSCT

At this point it might be worth dipping into what we know from HSCT research. I sometimes go into this with people with MS, or point them to where they can find out about it.

Just to be clear, the HSCT we’re talking about here – and throughout this article – is ‘aHSCT’. The ‘a’ stands for autologous, which means the stem cells used in the process come from your own body.

This kind of HSCT has been shown in a clinical trial called MIST to be a highly effective treatment for some people with MS: people with relapsing MS who had ongoing relapses despite being on a DMT.

In the MIST trial, the main drug that HSCT was compared to was natalizumab (Tysabri). What we don’t know is how HSCT compares to the other highly effective treatments, how well it works and how safe it is. The StarMS trial hopes to answer that question.

The evidence for HSCT in purely progressive MS is less compelling. It could help where someone’s MS is getting worse because of inflammation (either relapses or signs on an MRI scan). That’s because HSCT may be effective by suppressing inflammation in the brain and spinal cord. But there isn’t good evidence HSCT will repair damage already done to the central nervous system. That damage can happen without signs of inflammation.

Researchers have also tried to use large MS registries to compare HSCT and other DMTs in the real world, outside clinical trials. This data doesn't suggest HCST is more effective than natalizumab, ocrelizumab, alemtuzumab or cladribine in preventing relapses.

Could you access HSCT through a trial?

For some people with MS, a clinical trial could be a way to access HSCT. The StarMS trial has a number of sites taking part around the UK. The criteria for who can join the trial, and where your nearest centre would be is on the StarMS website.

If you think you might be eligible I’d recommend asking your neurologist to refer you. The trial team would need to confirm you can take part. And if you do, the neurologists and haematologists in the trial team would explain the benefits and risks. They’d also coordinate any specific care and monitoring before and after.

As I mentioned earlier, not everyone who goes on the trial will get HSCT. Some people will get a different, highly effective, DMT. The treatment you get is chosen randomly.

“Before the procedure I found out all about the possible risks and benefits. And I compared them with other treatment options I had. With HSCT, two things stood out for me: the risk of a serious infection and how it can affect fertility. Having decided to go for it, I wanted to know everything about freezing my eggs. The HSCT team put me in touch with a fertility clinic.”

Weighing the benefits and risks

HSCT is considered the ultimate re-boot of the immune system. Its advantage lies in the fact that it is, ideally, a one-off treatment. The risks involved are ‘front loaded’ around the time of the procedure. These risks are mainly related to infection from the fairly heavy duty chemotherapy. That’s what knocks out the immune system before it’s rebuilt with your stem cells.

The most common side effects from the chemotherapy occur in the immediate few weeks after the transplant. They can include sickness and vomiting, sore mouth and diarrhoea, hair loss and bladder inflammation. Most significantly, there’s the increased risk of infection. And as with other intensive procedures, there is a risk of death related to the HSCT transplant.

Read more about the side effects and risks with HSCT

Because most of the serious HSCT risk relates to infection risk from the chemotherapy, that risk goes down as time goes on. Some other potent DMTs continue to suppress the immune system (though not alemtuzumab and cladribine). So their risk of infection potentially goes up rather than down with time.

There can be some long-term side effects too. There’s a greater chance of developing cancer later in life. And as with alemtuzumab, there’s also the risk of developing other autoimmune problems in the future - although this is slightly less for HSCT than with alemtuzumab.

But it’s difficult to directly compare these risks with the other MS treatments outside of a clinical trial. That’s why the StarMS trial is so important.

Managing the impact on fertility

Another long-term impact from HSCT can be fertility problems. These can affect both men and women. Again, chemotherapy has this effect. It has the potential to cause fertility loss and premature menopause.

There have been cases of people becoming pregnant through intercourse after HSCT. But both men and women should be warned their fertility may be affected. They should have the chance to preserve fertility with egg or sperm collection.

Access to fertility services does vary across the country and in some areas – including mine - it’s only routinely available for people having cancer treatment. For anyone else, we need to put in individual requests for funding. Good access to these specialist services will be important as we look to offer HSCT locally – and for other HSCT centres that set up across the country.

“My neurologist told me Tysabri wasn’t working for me anymore and there wasn’t any other disease modifying therapy option for me. I didn’t meet the criteria for HSCT on the NHS, but with a lot of help I managed to raise the funds to get it in Moscow. My recovery from the procedure has been slow but ok. It included isolation at home while my immune system was very vulnerable. I paid for some physiotherapy privately, which really helped.”

HSCT overseas

There are undoubtedly still challenges to providing timely HSCT through the NHS, and the care and support people should have before and afterwards. But where there’s good evidence it could help it’s one of the DMT options available.

As anyone choosing their DMT knows, there’s lots to consider. For someone thinking about HSCT treatment abroad, there are some additional things to take into account. Of course there are the costs of care and travel. But setting those aside for now, there are things worth being aware of.

Firstly, centres offering HSCT overseas aren’t regulated in the same way that NHS services are. But there are internationally agreed standards. HSCT centres should be accredited with the International Society for Cellular Therapy and with the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). This is sometimes called a JACIE licence, named after the Joint Accreditation Committee of these two organisations.

The centre should be reporting their outcome data to the EBMT or a similar registry. Staff at the centre should have experience of treating patients with MS and be aware of the specific needs that patients with MS have. You should also check how the clinic is equipped to deal with medical emergencies such as serious allergic reactions or cardiac arrest - and that they have a plan should any complications occur.

As well as these details about care and standards, the centre should explain their procedure. The treatment regimes offered to patients abroad vary. Some places offer ‘myeloablative’ HSCT, which completely wipes out the immune system. Others offer non-myeloablative HSCT, which only partially wipes it out. Which one is used can affect how well the treatment works and the level of risk.

Travel, aftercare and recovery

Travelling and aftercare is important. So any overseas centre should give recommendations about how and when to travel after the procedure. And they should provide a ‘discharge summary’ to pass on to anyone else who provides care afterwards. A discharge summary should have details of the drugs used and mention any complications that occurred. It should also say exactly what’s needed for follow-up and monitoring.

As something to compare it to, having HSCT in the UK involves a hospital stay of around 4 weeks. Then you’d be discharged home but advised to shield for 3 months while your immune system recovers. During this time you’d usually be given antifungal, antiviral and antibiotics depending on local protocols.

Challenges of aftercare for overseas treatment

The arrangements for follow-up and monitoring of treatment done abroad can be challenging. A clear discharge summary can help.

For private treatment in the UK, we’d expect any routine follow-up and monitoring to be covered by the private healthcare provider and paid for by the patient. Though in an emergency the NHS would treat any patient.

When treatment happens abroad it’s not always clear who’s responsible for follow-up needed back in the UK. Neurologists may, reasonably, be reluctant to arrange monitoring for a treatment that they have no experience of carrying out themselves. When the procedure is carried out in the NHS, the monitoring of blood counts, measures to avoid infection and updating of vaccinations would be coordinated by haematologists. This is because they are familiar with the procedure.

So my advice to anyone having treatment abroad would be to make sure that you get clear instructions on the monitoring that's needed and the drugs used. On return to the UK, let your GP or MS team know so they can arrange appropriate follow-up with haematology. Ideally, you shouldn’t be discharged by the overseas clinic until your blood counts are starting to recover – that’s something to agree with the overseas clinic.

Recovery from the HSCT procedure takes some time, wherever it takes place. Because it lowers the immune response with such intensity, some people do experience a worsening of their MS symptoms such as pain, fatigue and spasticity. This should be temporary and there are specific guidelines to support ‘prehabilitation’ (getting prepared beforehand) and rehabilitation. That all goes alongside routine transplant care.

Read the in-depth medical guidelines for doctors who provide HSCT

HSCT now and in the future

It’s clear from conversations with my patients that there’s a lot of interest in HSCT. I think HSCT is an important part of our treatment armoury for active MS. And I’m looking forward to seeing the results of the StarMS trial. We need the clinical trial evidence so we have the best information on safety and effectiveness compared to other treatment options.

As I said at the start of this article, sometimes there’s an option that suits someone better. And that might be because of the risks from chemotherapy, the long stay in hospital or the 3 months of isolation. Or because there’s an alternative I can prescribe more quickly.

But I see a future where it’s easier for people to access HSCT where the research shows it could help them. There is definitely something very attractive about a treatment that only has to be given once and may be effective for many, many years to come without the need for ongoing treatment.

It’s vital that patients have access to information that lets them make the right decision for them. HSCT should be seen as a treatment option but not the only treatment for MS.

I welcome questions from my patients about HSCT and would encourage patients to discuss any questions they have with their MS neurologist or MS nurse.