Viruses and MS

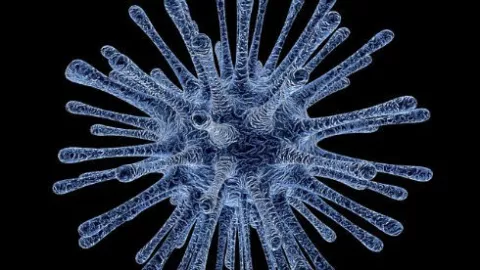

Viruses are tiny microbes that can make us ill. Some viruses might be involved in MS. One virus linked to MS is Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

About viruses

What are viruses?

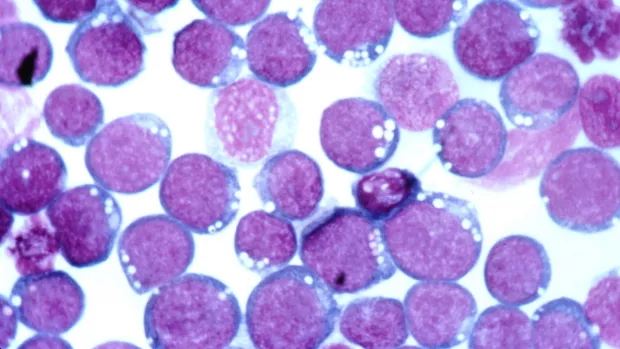

Viruses are the smallest of all microbes. They enter a cell and hijack it to make copies of themselves. Then, the copies burst out of the cell to repeat the process. The infected cells usually break down.

How can we fight viruses?

The immune system is our main defence against viruses.

Some types of immune cells can produce antibodies, which stick to viruses. This stops viruses from entering new cells. And makes it easier for immune cells to surround and destroy the viruses.

Other types of immune cells can recognise those infected with the virus. These are programmed to destroy the infected cells.

After we’ve had an infection with a virus, our immune cells can remember it. So they’re ready to fight it again. This is also how vaccines work.

Some viral infections are quite minor and our bodies fight them off in a few days, like the common cold. But some are more harmful and difficult for our bodies to fight.

Can we treat viruses with drugs?

Viruses are hard to kill with drugs because they're mainly hiding inside the body’s cells. Antiviral treatments can catch viruses when they burst out of cells. But each antiviral only works against a specific virus. Antibiotics won’t affect viruses.

What research is the MS Society funding on viruses and MS?

We supported a project showing EBV is linked to MS through T cells. The researchers took T cells from people with MS and people without MS, and grew the cells in a dish. They found T cells which responded to EBV also responded to myelin. This supports the idea the immune system is mistaking myelin for EBV. So, we better understand what’s happening in MS.

Now we’ve committed to raise funds for a new project focusing on EBV. The research will use blood samples to investigate whether EBV infects cells other than T cells and B cells.

About EBV and MS

What is EBV?

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a very common type of herpes virus. Nine in ten adults will be infected with EBV in their lifetime. Usually it causes no symptoms. In some people, EBV causes glandular fever, also known as mono (short for infectious mononucleosis).

EBV mainly infects cells in our immune system. It infects one type of immune cell and forces it to become a certain type, called memory B cells. These hide and stay in our immune system for the whole of our lives. So, after infection EBV lies dormant in our bodies for as long as we live. It occasionally shows itself when it makes more EBV virus.

Does EBV cause MS?

For several decades, we’ve known there’s a link between EBV and MS. Especially for symptomatic EBV infection (glandular fever, or mono). But proving EBV causes MS is challenging.

It could be that MS in fact makes you more likely to become infected with EBV, rather than the other way round. Or it could be that underlying genetic differences make you more likely to have both EBV and developing MS.

What’s the evidence?

EBV infection isn't enough to cause MS on its own. Most people are infected with EBV at some point and most people won’t develop MS. We think it’s a combination of genetics, something in your environment and your lifestyle that cause MS.

People with MS are more likely to have EBV antibodies than people without MS. This is a sign of previous infection with EBV. And people with MS are more likely to have had glandular fever (caused by EBV) than people without MS.

EBV and MS made the headlines in 2022. This study looked at over 10 million young adults from the US military. It showed people were always infected with EBV before they developed MS. And the process would show itself years after infection. This kind of study isn't enough to prove EBV infection is causing MS. But it’s the strongest evidence we can get without running trials to prevent EBV and see if there's a reduction in cases of MS.

Because infections trigger the immune system to react, researchers checked if this link to MS was specific to EBV. Or if it was just the immune system overreacting. Other infections didn’t show the same increased risk for developing MS. So, EBV isn't just a trigger for the immune system. There's a specific link that we don’t yet fully understand.

What does EBV do in MS?

There’s significant evidence of a link between EBV and MS. We think this is a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

But, we don’t yet fully understand what might lead from EBV infection to developing MS. Research has shown several possible pathways. It could also be a combination of these.

EBV might trigger immune activity leading to MS

Infection with viruses (like EBV) starts an immune response. We think in some people, this triggers the immune cells and leads to a cascade leading to MS. This may only happen in some people because of their genetics.

Some people with MS have different versions of certain genes. For example, genes that make human leukocyte antigens (HLA) on the surface of cells. The HLA found on body cells tell your immune system they’re part of you, so they’re not attacked. HLA also tell the immune system when the cells are invaded by infection.

EBV can use the HLA to infect immune cells. Some versions make it easier for the virus to infect the cells. From genetic studies we know these versions are more common in people who get MS.

Some versions of the HLA might make you more susceptible to immune cell attack. Then, when EBV infects it causes the immune system to react excessively.

Immune cells might mistake myelin for EBV

After a viral infection, immune cells remember what the virus looks like to attack it again. The immune cells could be mistaking myelin for EBV. Research shows parts of myelin look similar to parts of the EBV virus. Some people with MS have antibodies that grip on to both a part of the EBV virus and also part of myelin. Other people have immune cells that recognise EBV and myelin or other nerve proteins.

EBV might drive MS through immune cell infection

We know EBV stays dormant in immune cells after infection. These immune cells last throughout our lives. In MS, it’s these immune cells which mistakenly attack myelin. So, EBV could be continuing to influence the cells long after infection. Researchers think it does this by hijacking certain normally inactive parts of the genetic code. The activated immune system might become misdirected and attack myelin.

The dormant EBV hiding inside could be pushing a type of immune cells called B cells to attack myelin. Most existing disease modifying therapies (DMTs) work by killing or stopping all B cells. Perhaps the most important ones to kill are the EBV-infected B cells.

Can we prevent MS by preventing EBV?

We're likely many years away from finding out whether preventing EBV infection could prevent people developing MS.

If EBV does trigger MS, an EBV vaccine might prevent at least some people from getting MS who’d otherwise have developed it. But there’s currently no way to protect against becoming infected with EBV.

There's ongoing research to work out how best to do this.

What are the next steps?

- We need to be able to prevent people from getting infected with EBV and we can’t do that yet. There currently isn’t an approved EBV vaccine. A pharmaceutical company called Moderna are in the early clinical trial stage of developing an EBV vaccine. Any vaccine has to be tested with lots of people to know it’s safe and effective.

- And, it’s not clear if this vaccine would prevent EBV infection, or just prevent glandular fever. A vaccine only preventing glandular fever might not be enough to prevent MS, because some people with MS haven't had glandular fever.

- Once we can stop people getting EBV, we then need to know if that prevents MS. EBV is commonly caught in childhood. So, if we want to know whether an EBV vaccine prevents MS, we’d likely need to carry out a trial with children. We’d need to be certain about the vaccine’s safety. Then, we’d follow the vaccinated children to find out whether any went on to develop MS. This could take decades.

Could we treat MS by treating EBV?

Some research shows immune attacks in MS might be driven by EBV-infected immune cells. If this is true, we might be able to reduce immune attacks by getting rid of dormant EBV.

Some researchers think some existing DMTs like ocrelizumab might already do this by killing EBV-infected B cells. But, there may be other ways to get rid of EBV even more effectively.

T cell treatments

T cells are part of the immune system which can directly kill viruses. So, some researchers have made T cells that attack EBV-infected cells.

Researchers in Australia removed T cells from 10 people with MS. They then boosted the cells’ ability to recognise the EBV virus. And safely returned them to the same person. After 6 months, some of the participants reported less fatigue and some had an improved EDSS score.

Now, a larger scale trial for T cell treatment for people with MS called ATA188 is underway. This trial is slightly different as it uses EBV-targeted T cells from a healthy unrelated donor instead of the person themselves.

Antiviral therapies

Another potential way of treating EBV infection is with antiviral drugs. Some have been tested in MS, but more research is needed in this area. Amantadine is one antiviral drug that's sometimes used in MS. But it's only used to treat fatigue, and it’s not really clear how it works.

Are other viruses linked to MS?

Viruses other than EBV are linked to MS, though the link isn't as clear. And, they're less common than EBV.

- Human Herpes Virus 6 (HHV-6) is another type of herpes virus which may trigger MS. People with MS are more likely than people without MS to have had an infection with one version of the virus, HHV-6A. And, one study showed infection by HHV-6A more than doubled a person’s risk of developing MS.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is another herpes virus. Some research shows that people who were infected with CMV had a reduced risk of developing MS. This might be because CMV interacts with other viruses, like EBV or HHV-6A. But we don’t fully understand how this works. There’s a vaccine against CMV in Phase III trials by a pharmaceutical company called Moderna.

- COVID-19 doesn’t increase your risk of getting MS. But some people with MS could be at greater risk of getting coronavirus, or of complications if they catch it.