My father’s courageous battle with primary progressive MS

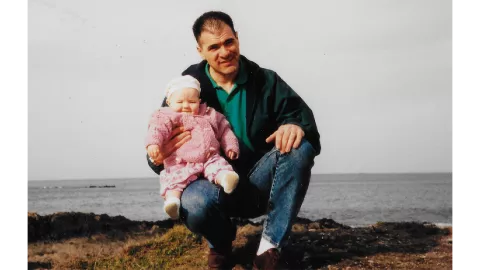

My father, David Fanning, died heroically on 21 July at age 56, after an 18 year battle with primary progressive MS. The stoicism he displayed in his fight is one to be admired. I hope this small glimpse into his life will inspire others, and highlight the severity of this type of MS.

His life before diagnosis

Originally from Ayrshire, my father, grew up in the 60s and 70s, spending most of his early childhood outdoors, getting up to all sorts of mischief. One memorable story, was when he got caught trespassing, and literally dodged a bullet fired from a disgruntled farmer.

As a teenager he attended Ayr Academy, where he was never far away from trouble, he had no problems sticking up for himself, or others, if there was good cause to do so. It was here, at 16, he met my mother, Jenefer.

In the late 1970s he left school, and became a police cadet. At that time a cadet was a full time employee, and underwent rigorous training. Approaching 18, he went on to work as a silver service waiter. His likeable persona garnered him enough tips for holidays to Amsterdam and Paris.

Early symptoms

In this early period, my father started to experience physical/mental fatigue, and involuntary leg spasms, which he brushed it off as nothing. He moved on to work in the warehouse of a big chain supermarket. This led to him being employed as head of security, earning respect from his manager for his, erm, direct approach.

By this time, he was married and had started his own family. My family uprooted to Aberdeenshire, where my father found work offshore. Known as a hard grafter, his name spread across the North Sea. The illness, however, began to surface, and eventually he found it more difficult to disguise.

His diagnosis with primary progressive MS

He was flown off a rig, paralysed down his left side. Months later at 38, he was diagnosed with primary progressive MS.

The scans showed the myelin in his brain, and spinal cord were already badly damaged. My father was understandably angry. No treatments/cure meant deterioration was on the horizon. But, he quickly grew to accept it. My parents were not going to allow the condition to affect their family. As a six year old it was confusing, but growing up his illness just became a part of everyday life.

He used humour to cope with his worsening MS

He would lack concentration, and suffer from severe bouts of exhaustion. Different medications were prescribed for his pain. He required the aid of a stick, sometimes falling as his legs gave way. We’d lift him off the ground, laughing, and unphased. He learned to cope with humour, and so did we. Determined not to sit in a manual wheelchair, he dragged himself around. But, eventually his mobility grew worse and he had to start using a chair.

His work, his driving licence, and walking his dog were all things he had to give up. We moved to an adapted house to accommodate his needs. With no external help, we assisted my mother in caring for my father. Every couple of years, he would lose some function, never once did he complain. Only, showing frustration as he lost the power to do something like shave his face, or write his name. In the course of eleven years, my father's world grew smaller, moving to an electric wheelchair with only some movement in his right arm.

Upbeat despite the pain

The pain got more excruciating, and he began to lose the function of his bladder, and bowels. Still, he remained remarkably upbeat. Sometimes referring to his speech as a ‘drunken Glaswegian'.

My father only got out once a week with wheelchair transportation. Heartbreakingly, never getting the use out of a mobility car that arrived months before his death.

With every setback we tried to remain positive

We were no Brady bunch, we struggled at times, he did require constant care. He was toileted, showered, dressed, shaved, hand-fed, manually transferred - you get the picture.

The last five months, his memory started to deteriorate, and it became too uncomfortable for him to sit in his electric wheelchair. Preferring his bed which was much less straining on his body.

He experienced dramatic weight loss due to muscle wastage, and lack of appetite. He struggled to chew and swallow. He was in immense pain. It was incredibly difficult.

My relationship with my father

I shared a very strong bond with my father. He was fun loving, and laid back in nature. I could call him, pretty much, whatever I liked. Taking the piss out of each other was an important part of the relationship.

I listened intently to his stories, and facts, while he pretended to listen to mine. Always willing to offer his intellect for school or college projects, provided he was credited. He was also very supportive - “Can I get a hug?” “No way.”

Music was his passion

Music was my father’s main passion in life. Any lottery win would have gone on iTunes gift cards. He was a regular concert goer before his diagnosis, and wrote to musicians - receiving autographs from the likes of BB King.

People only see what they want to see

Some people would not acknowledge my father in his wheelchair, thinking he lacked mental capacity. My father was the same person he had always been yet it was people’s ignorance that prevented this realisation.

Outside, he had support from his friends who attended the local day centre. He felt at ease in their company, as they too had their own experiences of the condition and physical disabilities.

No treatments to help my father

In the beginning, my father was hopeful in his research. After, years into his diagnosis he became disillusioned, reading about stories and treatments for other types of MS, and not his.

My father had the most aggressive form of MS, yet only one treatment (ocrelizumab) has become recently available on the NHS. Progressive MS ended my father’s life, and the future we had with him. He didn't deserve any of it, nor did we deserve to lose him.

David's daughter Pamela wanted to share his story to raise awareness of primary progressive MS and how it can affect families. If you'd like to talk to someone about any of the themes in their story call our MS Helpline freephone on 0808 800 8000

Help stop MS

Our Stop MS Appeal is raising £100 million for research to find treatments that stop or slow MS progression. By 2025 we want to have new treatments for everyone in the final stage of testing. But we need your help.